When the Supreme Court reached its landmark decision in July 2017 on the legality of Employment Tribunal fees last summer, the judges reviewed the evidence regarding the effect of fees on claims, and noted there had been “a dramatic and persistent fall in the number of claims” since fees were controversially introduced in 2013. They decided that the fees were wrong in several respects, and the Government immediately revoked them.

At the end of 2017, the number of claims lodged had risen by two-thirds since the Supreme Court’s decision. Recent tribunal data has shown that the number of cases brought by individuals in the UK increased by 118% in the three months to the end of March 2018, compared to the same period last year.

ACAS statistics on early conciliation make interesting reading. An employment law claim cannot move forward until ACAS has been informed, and early conciliation has ended. Early conciliation can be requested by either the employee or the employer; however, there is no requirement for the other side to have to agree to the early conciliation proposal. Total notifications have risen by 28%, or by 500 per week since tribunal fees were removed. The significant rise in the number of claimants after the Supreme Court ruling seems to confirm that the fees were acting as a deterrent. Removal of the fees has potentially lifted a significant barrier to access to justice in the employment law context, which has to be a good thing.

Much of the growth in cases has come from a return of what might be considered low-value claims, such as unpaid wages and holiday, which have increased by 137%. The returns on such cases might previously have been considered not worth pursuing, as many people who had valid claims could not afford to make them, so this increase is not surprising. A lot of businesses would gamble on the fact that they would not be taken to court. Now, many are reverting back to a more risk-averse approach.

A rise in tribunals was perhaps inevitable, given the legacy of cases that employees were reluctant to bring during the period of tribunal fees. This appears to suggest that disgruntled employees are now more inclined to take matters to tribunal, or at least, start the process, thus applying possible pressure on employers to settle. Fees were undoubtedly a substantial factor; the other reason for the decline in tribunals has been the recovery in the economy and job market. A lot will depend on the general state of the economy. In many areas or professions/trades at the moment, if someone loses their job they can probably walk into something better rather than fight a claim. If there is a continued increase in cases, it is likely to be either being due to a decline in the job market, or a statistical anomaly such as a glut of holiday pay or equal pay claims.

While claims are unlikely to increase to the level they stood at before the introduction of fees, the tribunal offices up and down the UK are very busy, with hearings regularly being cancelled at the last minute, and judgments taking much longer to produce than the four-week period users of the Tribunal system are told to expect. There is some concern regarding how the Employment Tribunal will cope with the number of claims being made, since the tribunals were slimmed down to deal with an average of 40-50,000 claims a quarter. If claims grow to 100,000 in that same time frame, it will increase the time required to dispose of them. Many tribunals have lost some of their part-time judges, and now that claims have been ramped up, the tribunal system lacks the resources to cope. The Court Service is recruiting, but that process takes a long time to appoint and then train them. They are mostly busy lawyers, so do not have a lot of time to give as part time judges.

Avoiding Claims

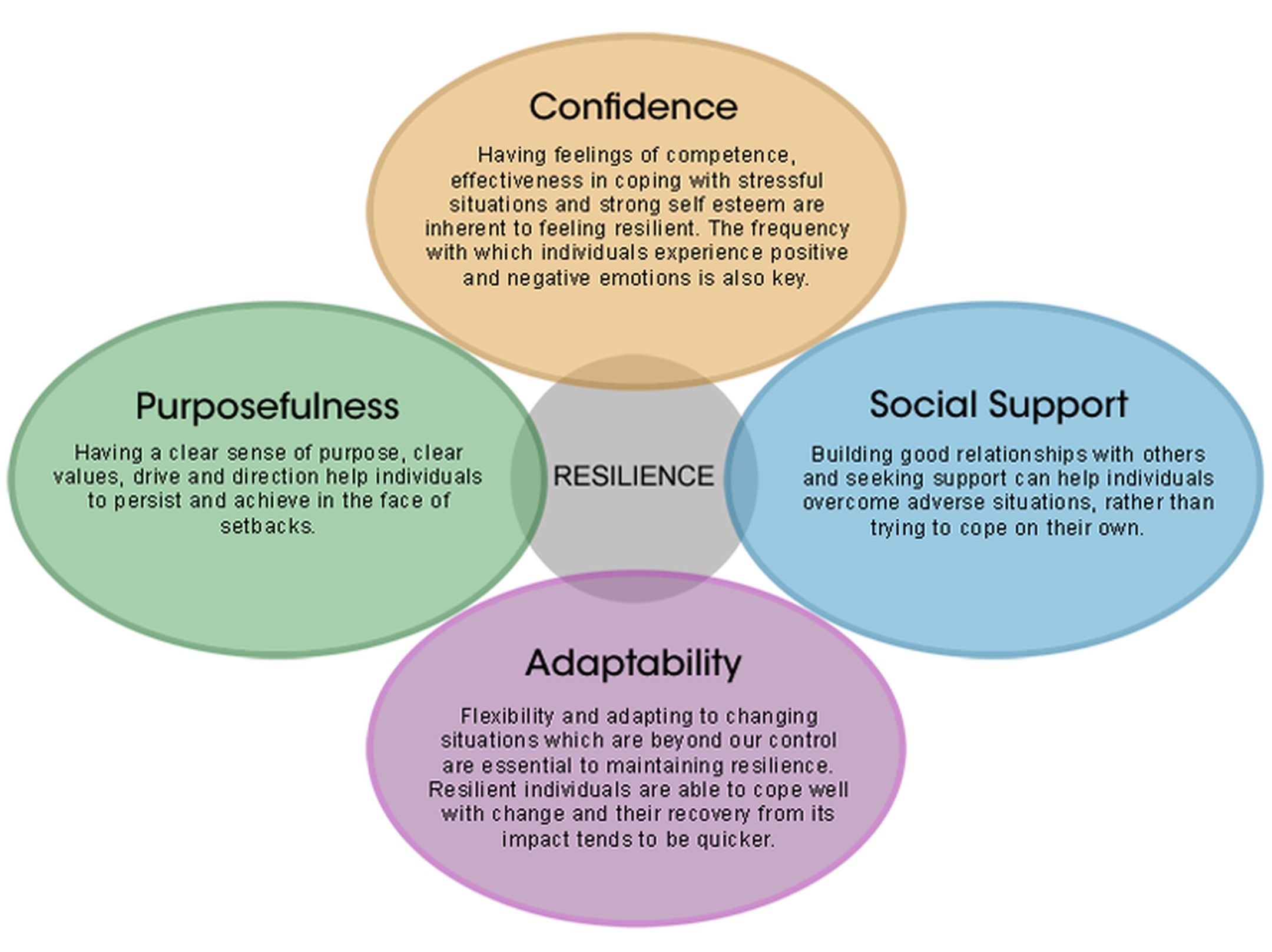

Losing a tribunal can have a big impact on a business’s bottom line, costing many thousands of pounds in compensation. This is in addition to the hundreds of hours of preparation and attendance, as well as the sleepless nights beforehand. There is also a substantial risk of bad publicity, and impact on employee morale. All these factors mean employers need to make sure that they have suitable measures in place to avoid a potential claim.

- The best way is to ensure all employment policies and procedures are up-to-date. Also, all employees are given well drafted written particulars of employment. Good procedures should help employers to reduce their chances of all but the most frivolous claims.

- All our clients have such policies and procedures, but in light of the sharp increase in tribunal cases, it would be prudent for employers to place a renewed emphasis on ensuring that all grievances and disciplinary matters carefully follow the procedures to comply with ACAS guidance. One of the most common causes of tribunals is not following a proper process. Make sure all staff; particularly Managers, are aware of the latest Handbook of Employment Policies, and who to ask for guidance if they are unsure on what is required to correct follow them.

- Careful recruitment of suitable people, who have the skills and attitudes for the job, or the potential to acquire them, will minimise the risk of substandard work and potential for time consuming re-training and dismissals.

- At the start of the induction period for both newly recruited employees and existing employees moving to a different job, the accountabilities and measures of performance in the job description should be explained fully. This ensures that employees are aware of what is expected from them, and how their performance will be measured. If an employee has not been properly trained, it is somewhat unwise to criticise substandard work. The employee can rightly argue that without the necessary knowledge and skills, it is not possible to do the job to the required standard.

- There is no legal rule that states probationary periods must be used, but they can be a useful tool for dealing with issues early on. The normal rule is that in order to qualify to bring an ordinary unfair dismissal claim, an employee must have been continuously employed for not less than two years. Employers tend to have probationary periods to assess the new recruit. However, if an employee has fewer than two years’ continuous employment, then they can still dismiss after a probationary period. That does not mean an employer is safe to dismiss them without fear of tribunal claims. There are 26 automatic unfair dismissal reasons that do not require two years’ service – such as dismissal relating to pregnancy, or health and safety reasons. Some of the reasons, such as whistleblowing, carry uncapped compensation. In dealing with employees with fewer than two years’ service, it is still advisable to use the probationary period review, and a basic three step dismissal procedure. If you do not, there is a risk that the employee could claim an automatically unfair dismissal reason, or dismissal for a discriminatory reason.

- Use your employee data to make sure your employees achieve their personal best. If an employee is underperforming, or is regularly absent, this could be a sign of a bigger underlying issue they may need help with. Reviewing employee data on a regular basis makes it easier to spot trends, and have early, informal conversations, rather than taking more heavy handed approaches that could end up at tribunal.

- Managers need to be properly trained so they feel able to make difficult judgement calls. Providing regular training and discussing HR issues with your Managers will help ensure they’re able to handle any problems employees might be having, before they escalate.

- Create and maintain a culture of open communication, as well as fair and honest feedback, so that problems can be nipped in the bud.

- Do not delay meetings, or hope problems will ‘go away’. Managers are often comfortable dealing with issues of misconduct, but can shy away from dealing with performance issues. An employee is more likely to turn their performance around if concerns are highlighted at an early stage rather than if matters are left to fester. Conflict can be difficult, but it rarely goes away of its own accord. Managers can be taught some basic low level mediation skills which should help diffuse conflict before it bubbles up.

- Treat employees equally, as it helps avoid resentment and discrimination cases can arise well before the two years required for unfair dismissal. Take care not to unduly criticise or humiliate a poorly performing employee in front of colleagues. If you do, there is a risk that the employee will resign and claim constructive unfair dismissal for breach of trust and confidence (assuming they have two years service).

- Consult over change, as disputes often arise because of poor communication. In many cases, such as redundancy, or changing contractual terms consultation is a major legal requirement.

- Encourage Managers to keep a clear evidence trail of how they addressed an employment issue, and their decisions about an employee. Audit trails are key to defending a tribunal case; plan ahead and always get everything in writing.

- If offering training and support results in a positive outcome, this is less time consuming and costly than going through a dismissal procedure and recruiting a replacement. Being able to demonstrate that an employee has been given support and the opportunity to improve will greatly improve the employer’s chances of making a fair dismissal if this becomes necessary.

- Ensure you get professional advice and support to avoid making a mistake, and then having to go for resultant damage limitation. Prevention is always better than cure.

Do what you can to follow your internal policies and procedures before something becomes a problem. If you are not feeling that patient or optimistic, then a Settlement Agreement might be the way forward. Performance management can be time consuming, and sometimes disciplinary issues are not clear cut. The alternative is for the employer to explore a settlement. This is not a DIY activity, as the rules around them are complex. Professional handling makes all the difference.

Dealing with a Tribunal Claim

Employment Tribunal claims are still rare but do happen to even the nicest and most cautious employers. It can be unsettling to receive a phone call from ACAS seeking early conciliation, and even more so to get a tribunal claim form through the post. At that point, emotion can get in the way of rational decision -making. All circumstances will be different, and we are more than happy to help employers to prepare for and win at Tribunal.

- Control the amount of legal costs and time that is poured into defending an Employment Tribunal claim. Do not allow a point of principle (for example, the wish to defend an unmeritorious claim) to take precedence over simple economics. Early resolution via ACAS may be the most financially viable approach.

- The other way to avoid a tribunal claim is by a Settlement Agreement, which can still be done after employment has ended, and tends to be more appropriate than an ACAS COT3 form, which do not tend to address complex issues such as Restraint Clauses or Intellectual Property, particularly for senior people.

- Make an informed decision about resourcing or settling the claim, based on the overall size of the claim, as well as being realistic about the chances of success in defending the claim. Bear in mind the amount of compensation that a successful claimant is likely to be awarded, and do the maths (with our help). Going to tribunal can be described as gambling at the casino of justice, so settling limits exposure and brings closure.

- Think through the wider implications of fighting an Employment Tribunal claim. These are the potential for negative publicity, as well as the time and cost of getting ready and attending the tribunal. This is likely to be two days for a simple unfair dismissal claim, and at least a week for a discrimination claim. Being in the witness box can amount to the worst fears of any employer. Even confident, competent Managers can be poor witnesses.

- Be aware that full vindication for either party is rare from an Employment Tribunal. Even if you win, you might still be criticised, or you might win some claims but lose others, e.g. the dismissal was fair but it was discriminatory in some respect.

It is possible that the Government will introduce another fee regime in the future, but that is unlikely to be for quite some time. Employers need to focus now on prevention instead of cure to avoid getting tribunal claims, and possibly discussing a commercial settlement where appropriate.

Our Consultants would be pleased to advise on any element of the issues arising from this newsletter.