With some non-essential retailers already returning to work, including places like car dealerships, it seems we are poised for another spate of re-openings over the coming weeks. The High Street will be opening up much more on 15th June, as many shops are able to reopen their doors, and there are strong indications that by 4th July pubs and restaurants may be able to open in some way.

There are a couple of very useful, free to download guides produced by the BSI and IOSH. For those of you who were not familiar with their work, IOSH is really the Institute for Health and Safety Consultants, but because that didn’t sound quite right, they have named it the Institute of Occupational Safety and Health.

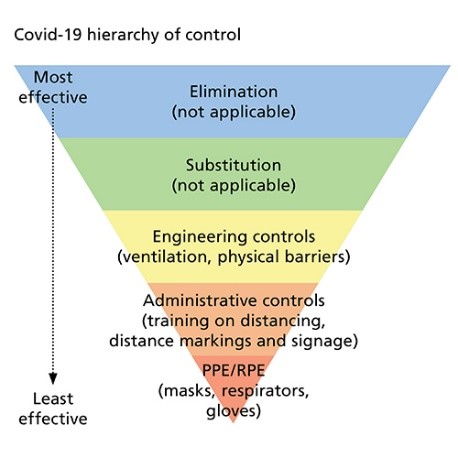

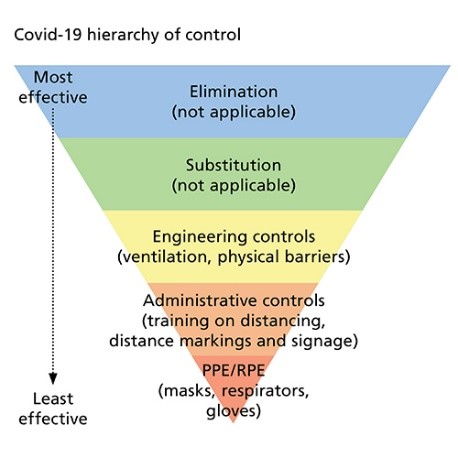

The risk assessment guide from IOSH includes this particularly helpful graphic, and some very good advice on how to apply it. We have already written a couple of articles on creating a Covid Secure workplace, and Managing the Return to Work, this article in particular is a useful addition to it.

Understanding how to carry out risk assessments is crucial if you are to manage this very difficult disease in your workplace. Doing this correctly will protect both your workers and yourself. Identifying each risk and area of risk, and mitigating it properly through a staged response is vital.

In the BSI document, called Safe Working During the Covid 19 Pandemic, there are some very useful definitions and they share some of the best practices. It is keen to point out that it is not a guide to risk assessments, but it lays out some very good principles.

As you would expect from an institution that is extremely good at specifying standards and defining them very tightly, they are very careful about the words they use, and how they should be applied.

So, for instance, early on in the document they tell the reader that the following verbal forms are used in the following way:

- “Should” indicates a recommendation

- “May” indicates a permission

- “Can” indicates a possibility or a capability.

Why is this important? Because such an approach much more tightly defines what until now look fairly loosely worded paragraphs. A bit like the legal definitions in a contract.

Later on, in their introduction, they say that they have used what the HSE recommend when developing a health and safety management system, a Plan – Do – Check – Act approach. Again, they define this quite closely:

- Plan what needs to be done for the organisation to work safely

- Do what the organisation has planned to do

- Check to see how well it is working

- Act to fix problems and look for ways to make what the organisation is doing even more effective.

Not a bad way of proceeding in the current climate to make sure that you protect your workforce, protect the organisation, and to demonstrate that you are taking safety and the risk of Covid 19 infection seriously.

Other areas that we particularly liked were clear definitions of the Clinically Vulnerable and Clinically Extremely Vulnerable in Section 3, Terms and Definitions.

The guide considers external issues that affect your workforce, such as methods of transport to work, which are not normally part of an employers’ concerns, but because of the pandemic are now very definitely fixed in their sights. It outlines very effectively how owners, Managers and other decision-makers should demonstrate leadership. And how they can encourage worker participation through communication, and opening ways for those with concerns and whistle-blowers to talk to Senior Management.

Categorise Work

For any organisations that are considering whether workers should return to the workplace, it suggests that organisations should divide work activities into three categories:

- can be done from home;

- cannot be done from home, but can comply with social distancing guidelines in the workplace, if practical adjustments are made;

- cannot be done from home and cannot comply with social distancing guidelines in the workplace;

In the latter category, employers must ask whether such an activity is essential for the operation of the organisation – it may only take place if additional controls (often PPE as the last resort) are implemented to mitigate the risks to health, safety and wellbeing at work.

Again, emphasising the principle of all health and safety legislation, it points out that it is not possible to eliminate the risks to Covid 19 entirely. But planning should aim to ensure the risk to workers is reduced to the “lowest reasonably practicable level”.

And, employers should make note of this, and communicate this clearly to their employees. No activity is 100% safe. Working from home, for instance, might be more dangerous for the workforce in the long run, as remaining static at home is not good for health. It certainly increases the risk of certain types of illness through physical inactivity.

But the employer’s job is to recognise control and mitigate the risk, making sure that their workers are protected as best they can.

Finally, and it is something that is often overlooked when planning, what happens in emergencies other than Covid 19? For instance, if there is a fire, clearly, especially in the case of panic, social distancing cannot be guaranteed. However, the need to evacuate the building quickly will almost certainly outweigh the risk from coronavirus.

Similarly, you may have to practice fire drills with a smaller workforce, and indeed make sure you plan carefully so that there is sufficient first-aid cover in the organisation, and that first aiders are trained in what needs to be done in the current circumstances.

RIDDOR

Both guides are excellent; however, we do take issue with the BSI in terms of one small but highly significant point. In section 10, they talk about the employer’s duty to report coronavirus under RIDDOR.

Coronavirus was legislated in March to be a notifiable disease, but the HSE has made it extremely clear that serious incidents need reporting where coronavirus is part of the occupation, rather than incidental to it.

What does that mean? The HSE website gives very clear guidance on the examples, of where an incident is reportable and where it is not. So, infections in the workforce are not reportable (though a widespread COVID-19 infection within a working team for instance may be classed as a RIDDOR dangerous occurrence and should also be reported to your local authority, who can give proper support and direction). But, where a worker works directly with coronavirus, for instance in a laboratory, the dropping of a vial of coronavirus and its escape into the environment is reportable.

A policeman contracting coronavirus by contact with the general public is not. There is also a very high level of proof required to identify that the coronavirus has been contracted at work, and not anywhere else.

This is not the impression given by the BSI, and we disagree with their guidance in this part of the guide.

Otherwise, both documents are excellent documents and well worth reading. The links to these documents are as follows:-

IOSH: Returning safely – Covid-19 Risk Assessment Guidance

Our Consultants would be pleased to advise you on any element of the issues arising from this newsletter.